Measles News:

We’re seeing two main responses to measles from health departments: general disinterest or large-scale quarantine for non-vaccinated people, usually kids.

Around the U.S., most measles cases we have seen that affect our clients’ businesses are one-offs. They’re international travelers who just returned home, or people who are part of small outbreak pockets. They’re either our clients’ employees or guests who have visited their businesses while infectious. For most of these, we’re seeing health departments go public quickly, but only with a list of places the sick person was during their infectious period. It often includes multiple businesses they’ve shopped at, community organizations like churches or synagogues they’ve visited, and healthcare facilities where they sought medical attention. In most of these, the health department isn’t requiring vaccination or quarantine for exposed employees, even if they worked with the sick person.

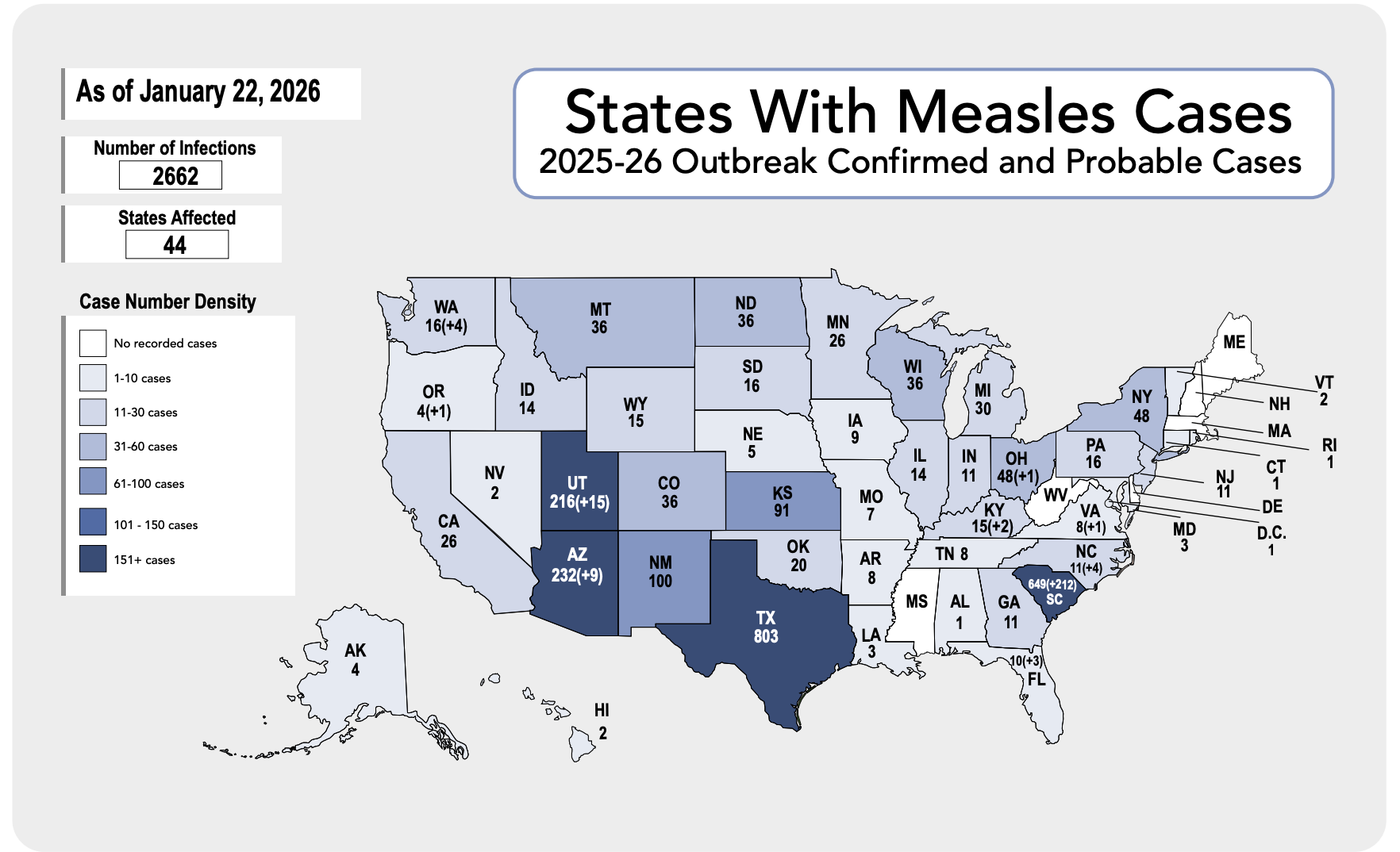

The situations we’re seeing them react more strongly to are school exposures - when a child or staff member went to school sick, and there are dozens or even hundreds of unvaccinated children who were exposed. In these cases, we are seeing health departments require quarantine for those who aren’t vaccinated, in part because children are extra vulnerable to measles. It’s a good thing, too – in South Carolina last month hundreds of kids had to stay home from school for 21 days after exposure, and dozens of them later developed measles symptoms. The quarantines there and at the Utah-Arizona border keep coming, especially for unvaccinated school children.

It’s important to keep in mind that we’re seeing really varied responses across the board from health departments. Some are really active and see themselves as key players in the absence of federal leadership (due to cuts and the government shutdown), while others are understaffed and overworked, just trying to stay afloat with the bare minimum. If you have measles in the area, you should be prepared for either end of the spectrum.

As of yesterday, the U.S. left the WHO. This article from TIME Magazine breaks down whether it’s actually possible (it’s never been done before), what it means, and what will change here in the U.S. and around the world as a result.